Edinburgh 1787, Scotland, Robert Barker invents a totally new way to observe a city. With him, space, time and meaning are controlled and the audience gets for maybe the first time, the complete illusion of being immersed, invited, in a remote place. His invention will then know a great success and be spread all over the world. New technologies will enrich the process of immersion, the spectacular aspect of being elsewhere without moving. Until with our state of the art devices, we still experiment the same protocols that Barker and his followers. This wonderful space and time machine is a Panorama, and it simply changed the way we observe the world.

Most often in the bibliography, panoramas are described as a giant surrounding painting and send back to the vintage vision of the XIX’s century. It’s generally sent back as a forgotten attraction in the steam of the industrial revolution. Nothing is more wrong: as soon as photography was invented, it was seized by the panorama, inventing new view cameras for new, larger « formats »; the Lumiere brothers filed for a patent for 360° takes on a single plate with a continuous image allowing for an overview; the Photorama. When the cinema was invented, it was immediately adopted: Grimoin—Sanson’s invention, the Cineorama in 1900, allowed viewers to experience a virtual balloon ride. Six simultaneous machines projected the film of an ascension inside a cylinder while the public stood on a platform built to resemble a basket.

The panorama ran out of interest with the advent of the cinema and great rotundas were closed. But the singular effect produced by the large « format » image on the audience was set to bring them back. First, they reappeared in planetariums, then in cinemas with a first endeavour proposed by Abel Gance’s Napoleon, created in 1927. This film actually contains only a single sequence projected onto three screens, but it was the first step. Then Disney in its amusement parks recreated a kind of rotunda for a 360 vision experience: the Circarama. The Polyvision system, developed by Emile Vuillermoz relying on the 4:1 « format » proved too complicated to put into place and maintain and was finally abandoned. Several multi-screen projects were developed however and although it would be tedious to enumerate each one, we can remember the Vitarama (1939, eleven cameras), the Cinerama (1952, three cameras), the Circlorama (1958, eleven cameras), the Hexiplex (1992, six cameras). The 360° projection became a theatrical tool, which Australian artist Jeffrey Shaw, founder of ZKM in Karlsruhe offered the Wooster Group with There is Still Time… Brother (2007), for example, with installations where the viewer/spectator explores a panorama through a virtual peephole. The panoramic screen, then the dome create an illusion of immersion, as the gaze is always on the image. It is the envelopment effect. Not only relying on the projected image, it is also achieved with sound and imagination. In a classical theatre installations or at the cinema, the place of action, the diegetic space is contained by a frame which imposes a gaze direction. All visual and acoustic elements arise from the frame. But with the arrival of stereophonic sound and its integration into the cinema, there was a first overflow. The notion of off-camera was introduced: prolongation of the action, the diegetic space continued away from view. It means that the notion of space/time and action can be questioned. The classic occidental way to understand a picture, like a painting, is paused frame in time. It has been always the same, and this is a great subject of meaning. The medieval paintings can be understood as mnemonic scenes where many moments in times are superimposed. But nowadays, this knowledge is sometimes forgotten, we see a frame like a photo taken at a certain time.

Panoramas and its descendants put the spectators into movement, and this way includes time. The image occupies the spectator’s entire visual field and when the image is limited by structural imperatives, the runoff continues off-screen, carried by the sound and the imagination. And why not completely obliterate the frame, embrace the « off-format »? In theatre, for example, the frontal disposition was challenged so that, at the beginning of the 20th century, new forms were created which allowed more immersion in the show. The architects of the Bauhaus, Andor Weininger with the Kugeltheateer (1926-1927) and especially Walter Gropius with the Total Theater (1927) used these utopian projects to break the frontal view and spread the show in the entire space of the theatre, itself mobile. Closer to us is Jacques Polieri, who, in the 70s and 80s, thought up projects such as the “Theatre du Mouvement Total a Osaka” (1970), where seating and stage move, interact and allow the audience to dive deeper into the action. For this avant-garde set designer, the audience must experience the emotions physically. The set must engage the entire sensorial palette. In the mid-20th century, it was common to own your own small portable panorama: folded in accordion, the Leporello showed the world in the form of a travelling inventory of cities. We were able to buy disposable cameras to create 12 x 36 panoramic image « formats ». Nowadays, anyone can make their own panorama. It was even the selling point of a brand represented by a fruit, expert at pretending it is at the forefront of each innovation. With a simple telephone, the world is captured at 360° and deployed in the frame of the screen, bit by bit or in immersive technology such as Oculus Rift or Google Cardboard. From a distance, two simple squares; up close, eyes on the screen, a world is deployed, without limits, without a frame.

Panoramas as a built structure as they were in the XIX century or as immersive devices like in the XX century or as virtual experiences like in the early XXI century are disrupting the audience’s notion of time and space by providing a powerful feeling of immersion. But it has never been without meaning. Since the first panorama, and moreover with the following one, a story was always brought with the picture: the size of the city, the importance of a remote event, the remembering great battles, and spectators were put in the middle of the story, they were nearly part of it. With our new devices, we record in 360 our own story and we post it on the internet giving the possibility to everyone to see the world through our own eyes.

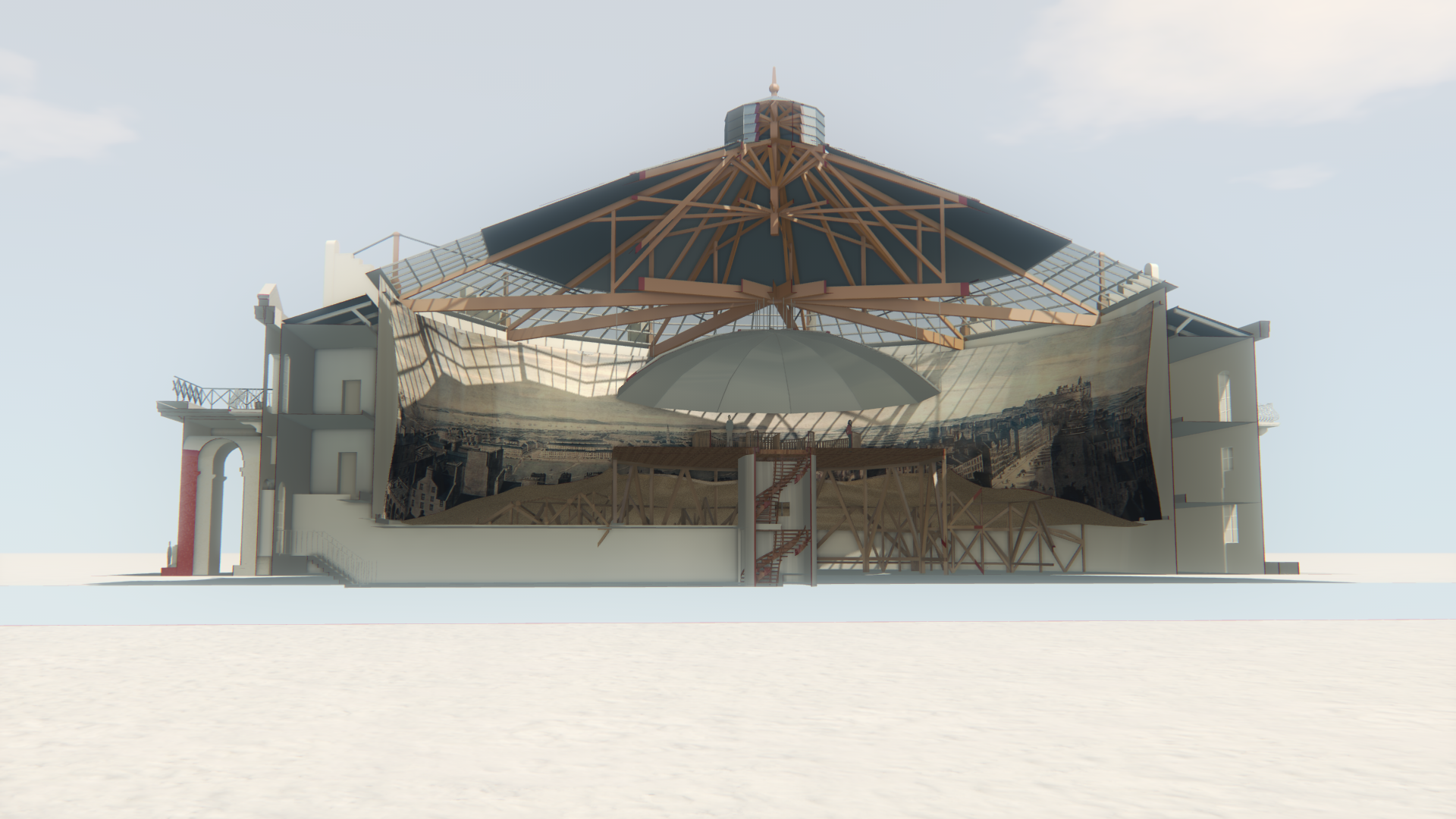

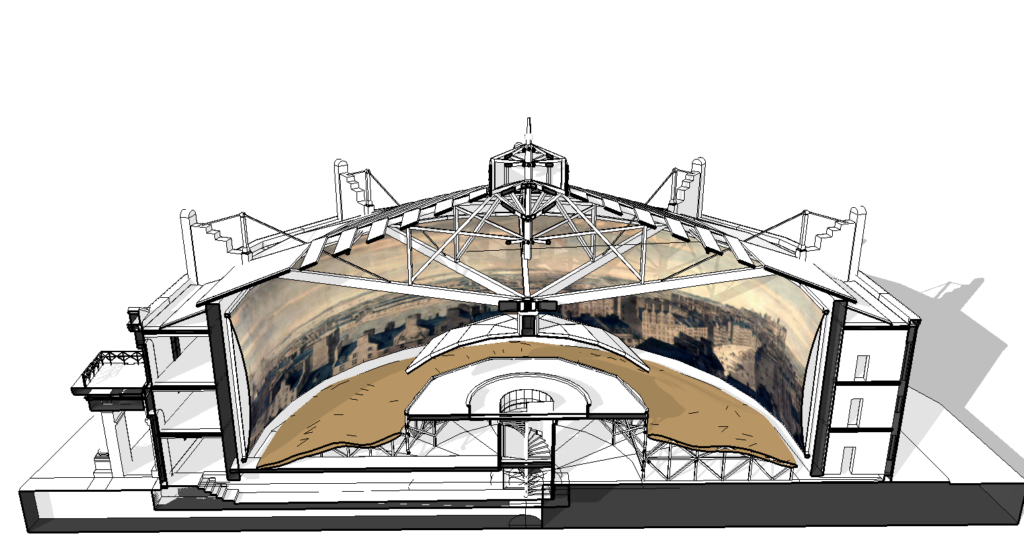

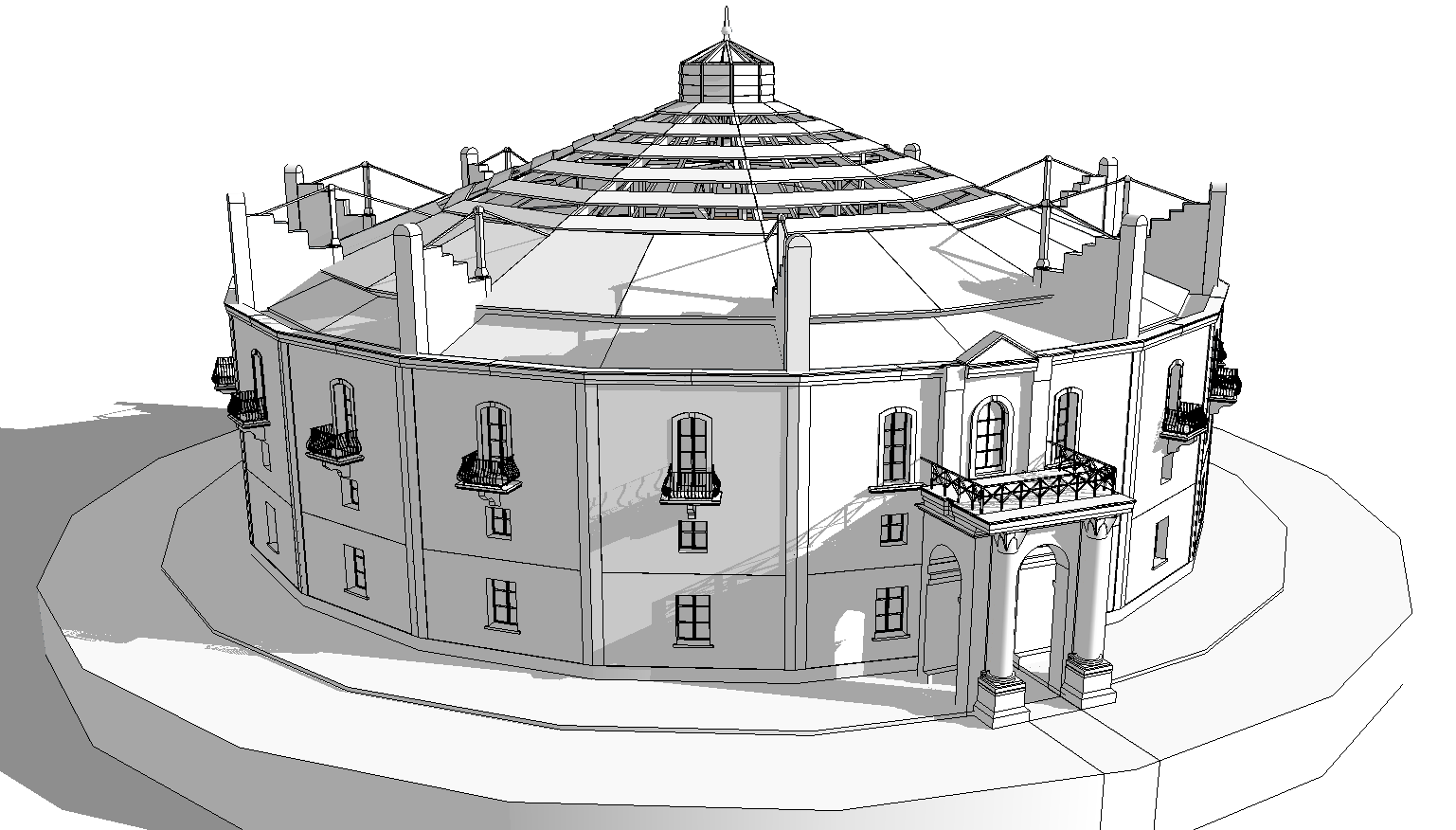

In this article, we will recall the great issues of the panoramas as an immersive experience, as architectural device and we will follow the main topics from the origin to today. We will then propose a travel through space and time to experiment a demolished panorama with a virtual visit.

References

BAPST G., Essai sur l’histoire des panoramas et de dioramas, Imprimerie Nationale (Paris), 1891

BENOSMAN R., Panoramic Vision: Sensors, Theory, and Applications, Springer, 2001

HYDE R., Panoramania!: Art and Entertainment of the All-embracing View, Trefoil Publications Ltd, 1988

To quote or to get the full version of this article

Laurent Lescop. 360° vision, from panoramas to VR. Tom Maver. ENVISIONING ARCHITECTURE: SPACE / TIME / MEANING, Sep 2017, Glasgow, United Kingdom. Published by the Mackintosh School of Architecture and the School of Simulation and Visualization at the Glasgow School of Art, 1, pp.226-232, 2017, ENVISIONING ARCHITECTURE: SPACE / TIME / MEANING. 〈hal-01584883〉